Assessing English Standards in Malaysia: An Analysis with the CEFR

Often in Malaysia, people talk about how our standard of English is either sufficiently good that it is the basis of a thesis for investment, or they say that our English is abysmal and needs drastically to be improved – discussions go on and on, and people fight, oftentimes in what seems like a battle for the soul of our society.

But what does it mean, actually, that our English is good or our English is bad?

Some say that Malaysia aligns itself to international standards in creating its curricula, but others squabble day in and day out, constantly complaining about the quality of English amongst graduates who come into the workforce, observing that many of them lack basic skills that they would expect graduates to have. How can it be possible that Malaysia calibrates itself to international standards while at the same time its graduates languish in terms of their English language proficiency?

But at the end of the day, who’s right?

As it turns out, investigating a little further tells us that the answer is both.

Here’s where the subject of our blog post for today comes in: The Common European Framework for Reference, otherwise known as the CEFR.

The reason that I’m making this comparison today and telling you about CEFR is that Malaysia uses it to calibrate SPM writing standards.

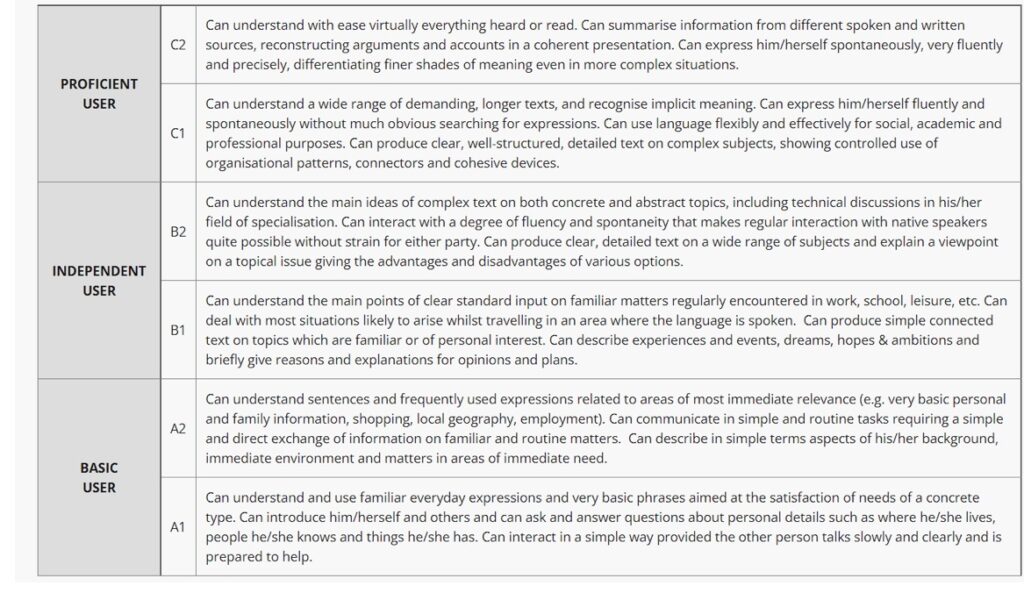

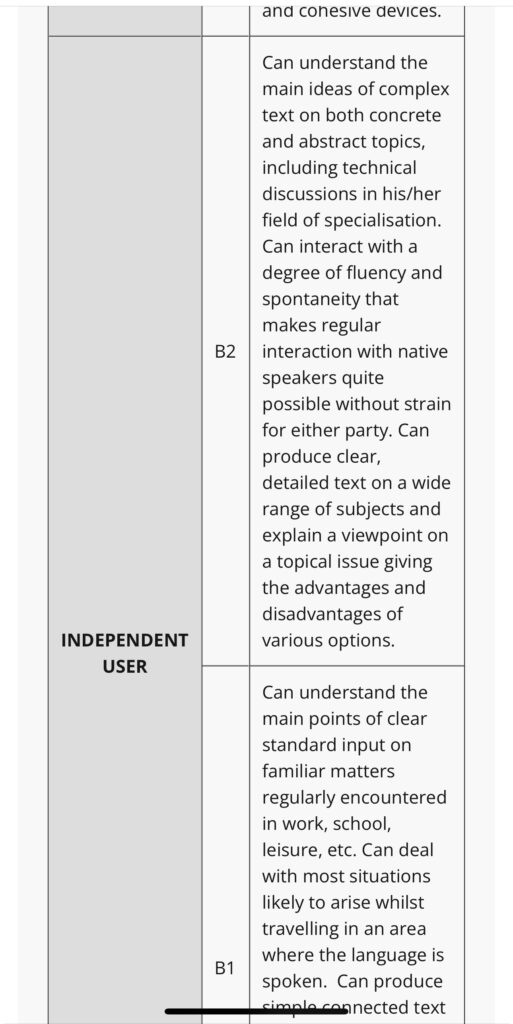

The CEFR operationalizes language proficiency in accordance with six dimensions, from A1 up until C2. It is an international standard that is utilized by examining bodies across the world in order to designate proficiency levels and descriptors that students attain after courses of study, and it is used also in designing curricula so that students can reach a certain defined standard.

Source: https://www.cambridgeenglish.org/Images/126130-cefr-diagram.pdf

CEFR operationalizes English proficiency according to numerous level descriptors, providing explanations of what a user of the English language should be able to do at every single possible level that has been defined under the CEFR framework.

As you can see in the image below, here is what English proficiency as demonstrated by a proficient user, aka C2, should be able to do.

As you can see, this is a relatively intuitive sense of what we would want a competent communicator in English to be able to do, to summarize, to understand, to be able to comprehend complex and even abstract topics in the context of a discussion without any effort whatsoever, and to be able to, in turn, produce language in such a way that there are no difficulties in receiving meaning at all on the part of a listener.

Moving beyond this intuition, however, we can begin to identify distinct categories as we move down the scale.

As we can see in the level descriptors for B2 instead, a B2-level communicator can understand the main idea of a text, but may not be able to necessarily understand every single thing, or may find difficulty in catching the nuances of what is being presented to the extent that they may not be able to accept, process, and deal with finer shades of meaning to the extent that they can give an informed response. In other words, there is a difference in communicative competency as well as in extent of comprehension as we move through the levels.

Relevance to Malaysia

Where this gets interesting is what you consider that the CEFR is used for. There are various clear examples of this, both in the Cambridge IGCSE exams and also in the present subject of our discussion, which is the Malaysian Curriculum as operationalized in SPM Writing Grading Guidelines, both of which I will show in the next section.

Let’s first consider how CEFR is used in calibrating SPM standards.

Consider the document available at this link. (https://jpnkelantan.moe.gov.my/tu-muat-turun/category/109-bahan-latihan-common-european-framework-of-reference-cefr?download=245:spm-instructions-for-writing-examiners-v3)

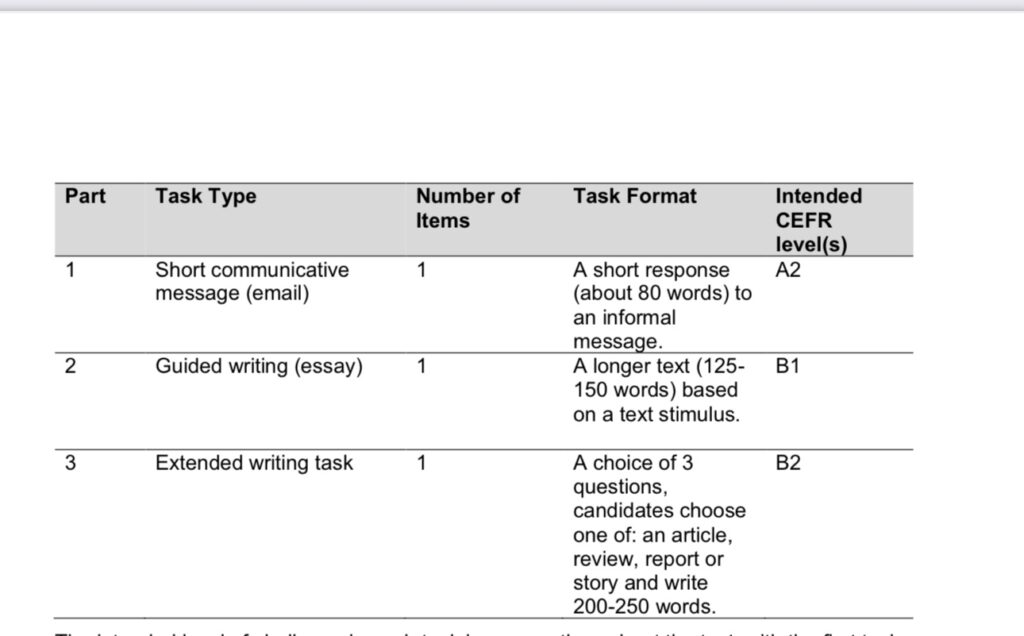

This is an examiner’s guide for teachers who are in charge of marking exam scripts for SPM English writing examinations; it can be easily found on Google when you google “CEFR Malaysia SPM”. It outlines the different sections of the SPM English examination and also establishes a scale of achievement that is measured by every individual component of the exam.

Consider the following section that tells us about the curriculum design and the intended scope of assessment covered by the SPM writing exams.

Based on this, you can see that the main focus of the SPM English examination is to assess students within the B1 to B2 level range.

As an external curriculum, and therefore as a motivator for students, we can, by extension, guess that this is the standard to which the Ministry of Education of Malaysia wishes for students to aspire towards. As the criteria also indicate, assessment spans from A1 to C1 according to the CEFR scale, which suggests that at the very top range of the candidates that take the SPM examinations, we could expect communicative competency to be at the C1 level.

This might not seem too relevant to you, but a small comparison may help you see why is relevant to you, particularly if you’re choosing the schooling system that you would like your child to be a part of.

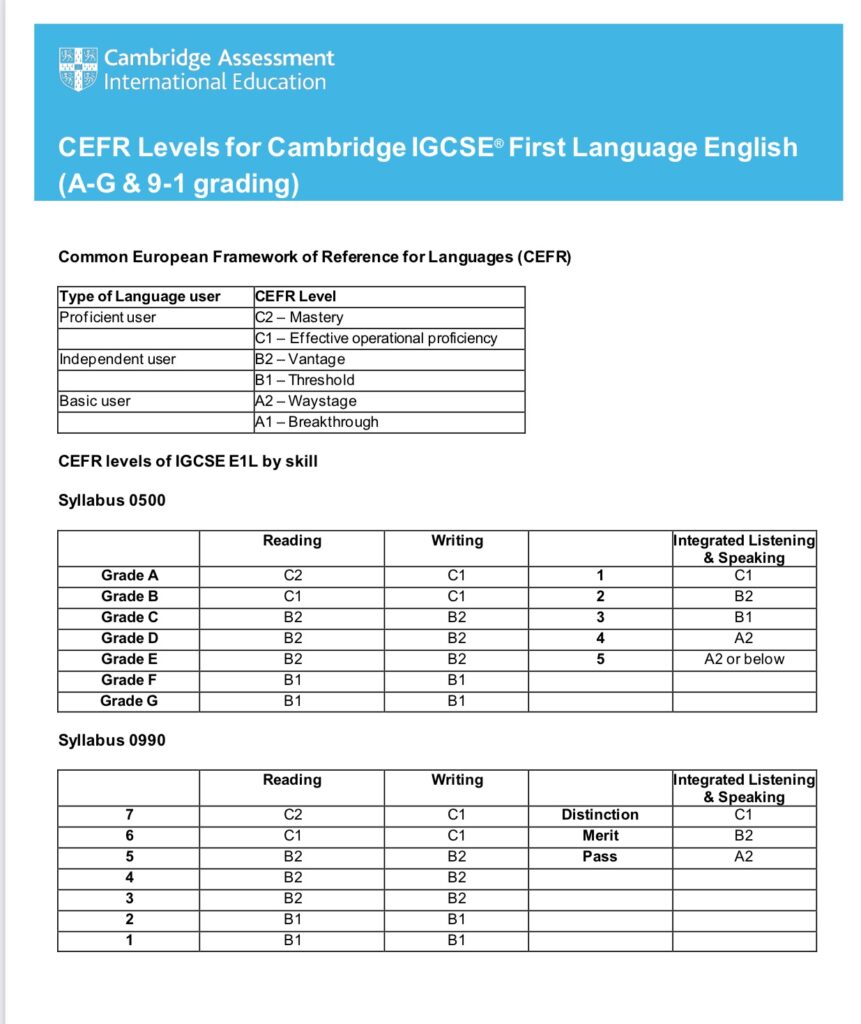

This is why we will compare this CEFR guidance for the SPM English examinations with the Cambridge IGCSE First Language English examinations. Consider the picture below, taken from the website of Cambridge Assessment International Education.

Recall for a minute that the SPM English Assessment Scale indicated that the scale went from A1 up until C1 at the very highest possible level, and also indicated that the core focus of the curriculum was from the B1 to B2 level.

Now, have a look below.

Source: https://www.cambridgeinternational.org/Images/152745-cefr-levels-for-cambridge-igcse-first-language-english-0500-and-0522-.pdf

As you can see, in the First Language English curriculum, you will see that a C1 in Competency corresponds to a Grade B, while the very bottom level of achievement for a B2 is a Grade E for the Writing exam. What does this mean?

This means that the SPM English exam is targeted in such a way that the majority of candidates who take it and succeed in obtaining the qualification, barring the top levels of achievement, can be expected to achieve a Grade range from G until C on the IGCSE First Language English examinations.

Considering that the IGCSE First Language English exam doesn’t account for people who are perfect in English either, is it really a surprise that most SPM candidates are, by people’s modern estimation, not particularly competent in the English language?

Even if you just barely passed the IGCSE First Language English exam, you can be expected to demonstrate a level of communicative competency that is on par with or exceeds the level that would be expected of people who are scoring at the A level for the SPM English exams.

Now, this doesn’t mean by any means that the people who are all doing the SPM are all of an equally bad standard by no means. It just means that even if a particular student scores an A+, then it simply means that they are at a B2 level or higher.

It is entirely possible that they could be at a higher level of communicative competency, but it’s simply that the test does not measure the level of capability that is correspondent to that level of achievement. It also means, by extension, since exams serve an extrinsic motivating factor for students to study and to direct their efforts, while simultaneously serving as the framework of ground truth and bar of excellence to which students should aspire, and accordingly teachers act in order to operationalize and develop, students in Malaysia are collectively aspiring to a lower standard relative to their international counterparts.

This is the case both in terms of the level of expectation that is hoisted upon them by their curriculum, and accordingly the level of instruction that is delivered by instructors who are playing towards that particular standard, and even then cannot be expected to achieve it to the greatest possible extent, introducing yet another potential inefficiency that lessens the prospects of the average student of English in Malaysia, reducing it down to the bare bottom.

In other words, this means that the curriculum and by extension the governance that operationalizes it as a whole does not serve, necessarily, a causative impact in helping students to reach a level that is concordant with what we would call international standards, except on the level of lip service, simply because it operationalises the curriculum to fulfill CEFR B1 to B2, which is not a high standard and does not concord with standards that would place Malaysian students on a level that would allow them to meaningfully compete with their counterparts in an increasingly internationalized workforce that has lost almost all of its insulation from the forces of globalization.

One could very well make the case that English is a second language for most learners in Malaysia, and hence that this is just the expected result that we should accomplish and that there is no need to go further. But if you truly believed that, you wouldn’t come out in such droves in order to talk about how English proficiency is lacking in this country.

You would not be writing to our newspapers talking about how we need to improve our English.

You would not be constantly wondering why people are unable to perform the most basic tasks in English when in fact your national curriculum and what you have allowed it to become is not concordant with the needs of the internationalised world that you live in and cannot avoid by simply saying that you are a Malaysian citizen and do not need to aspire towards international standards because you are not insulated from the world, you are very much a part of it and claiming national identity and pride in it while at the same time falling short of the standards you need to achieve in order to reach the goals that you aspire to attain in other areas is unfeasible and will not ultimately lead to the result that you want.

Accordingly, with respect to the paradigm of international competition, the curriculum in and of itself, despite what the Ministry of Education has said or has not said, is woefully inadequate to meet the needs of English language communication in the modern era, even if English is taken as a stand-alone subject, even beyond the consideration of taking it away from English-medium consideration altogether, sidelining it, and making it only the province of the rich, powerful, and supremely educated.

Of course, this is not counting the students who perform at the very top levels of achievement (A+ for SPM), who clearly demonstrate communicative competency at at least the B2 level.

Of course, such students might do well according to the grade that they receive, but there are several dangers associated with being grade-conscious in this case. For instance, if students receive an A+, and think that they are at the highest possible level already, that would suggest that they are only basic communicators in the English language, able to hold conversations and understand main points with no issues, but incapable of communicating deeper shades of meaning.

Accordingly, the curriculum would restrict them from reaching the higher levels of attainment that one might expect from highly effective communicators. Secondly, we might expect also that the relatively low standard of the curriculum means that if students simply aspire to the bare minimum of following what has been told to them, that they will not extend their abilities far beyond where it is that they need to go. Accordingly, the net result would be that they might stagnate in their progress, and not go any further, which reflects a disservice performed to them and to Malaysia as a whole, even as the countries around us aspire for the world standard.

So what have we discussed so far? We’ve discussed the CEFR framework. We’ve discussed where Malaysia’s education system places in the context of that CEFR framework. And we’ve looked at a comparison between the Malaysian education system and the Cambridge First Language English exam system, which allowed us to develop an understanding of the relative level of the SPM curriculum to the IGCSE, which operationalizes where we are in the context of the world.

What is clearly shown is that Malaysian students are expected to perform only to a lower level compared to their counterparts in international schools, and that’s not even speaking about how our teachers are recruited and whether or not they are able to successfully deliver the curriculum in the first place.

Having said that, this doesn’t mean that excellence can’t exist in Malaysia, because there will always be people who will push the boundaries and go beyond expectations to reach international standards on their own.

What’s clear to see though is that levels of ability that exceed the norm aren’t expected by this system, and neither are they well-served by this system, which caters poorly to people who wish to go above and beyond, forcing them to find excellence in English outside of its confines rather than within it, as is right and proper.