There are often many situations when I have to correct my students’ English. Perhaps they forgot to use the correct tense – perhaps they forgot to make sure that the subject and verb agree.

This is normal – we are human, and we are flawed.

It is not all that common that I find occasion to correct the English of someone who has written an article about the factors behind what they perceive as a drop in nationwide English proficiency or, for that matter, someone of Mariam Mokhtar’s infamy, though.

Consider this recent piece titled “Poor teachers, politicians to blame for bad English” that she did about English proficiency in Malaysia, the country where I live (and also the country that I’ve seen to most regularly participate in extensive debates about this issue), in which she blames politicians and educators alone for >>what she sees<< as low English proficiency in Malaysia.

While I respect the fact that she has good intentions, there is a famous quote that summarizes the entire situation.

…Yup.

I wanted to like this piece because it does advance a cause that I do care about: English proficiency.

However, I was unable to, because while perhaps Mokhtar’s intentions are good, the execution, reasoning, and delivery of this piece were disappointing from start to finish. All in all, I think it is a horrible piece, and I think that firstly she should retract it, and secondly I see it and the fact that it’s been shared over 500 times as evidence that as Malaysians and as human beings at large, we need to start demanding higher standard critics of our society or at the least refrain from sharing works that ultimately do not further the cause of developing productive or intelligent discourse in our world.

What is the piece about?

The piece is a piece about what Mokhtar sees as the decline of English proficiency amongst Malaysians.

Here is the text of the post, taken from Free Malaysia Today:

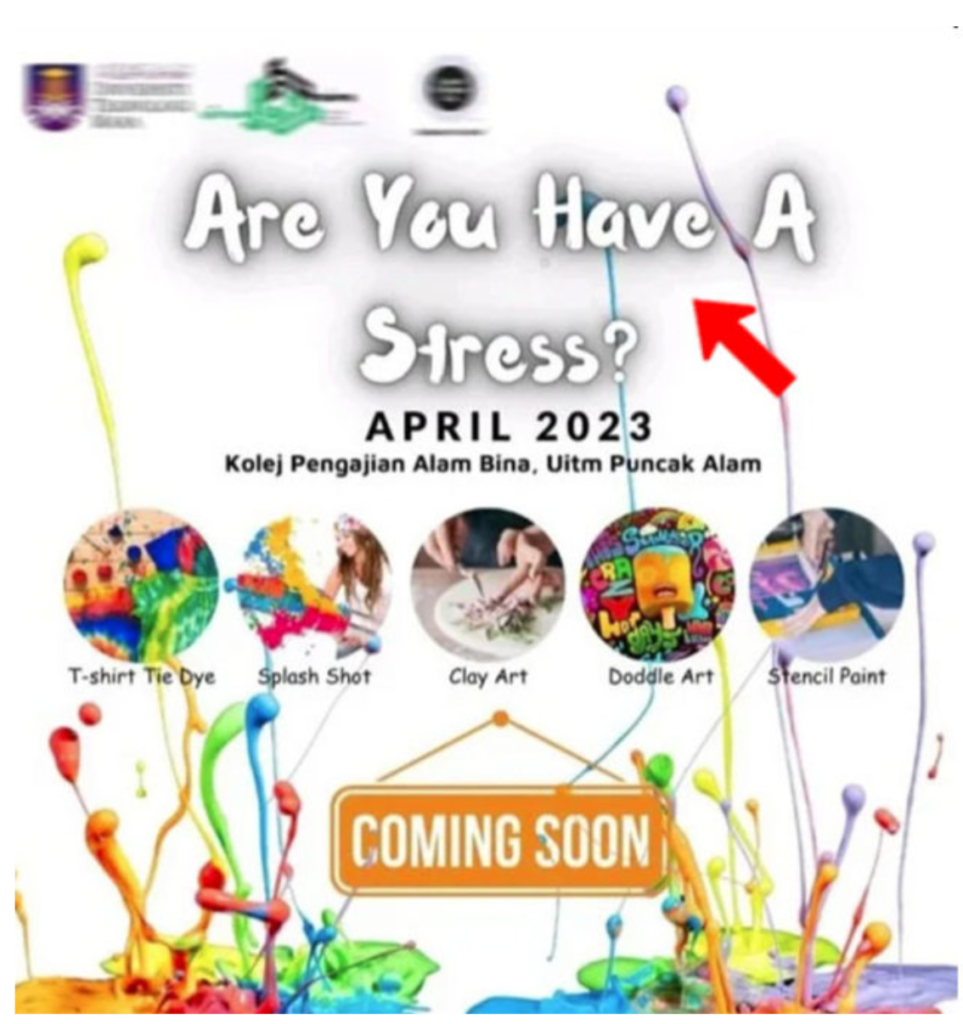

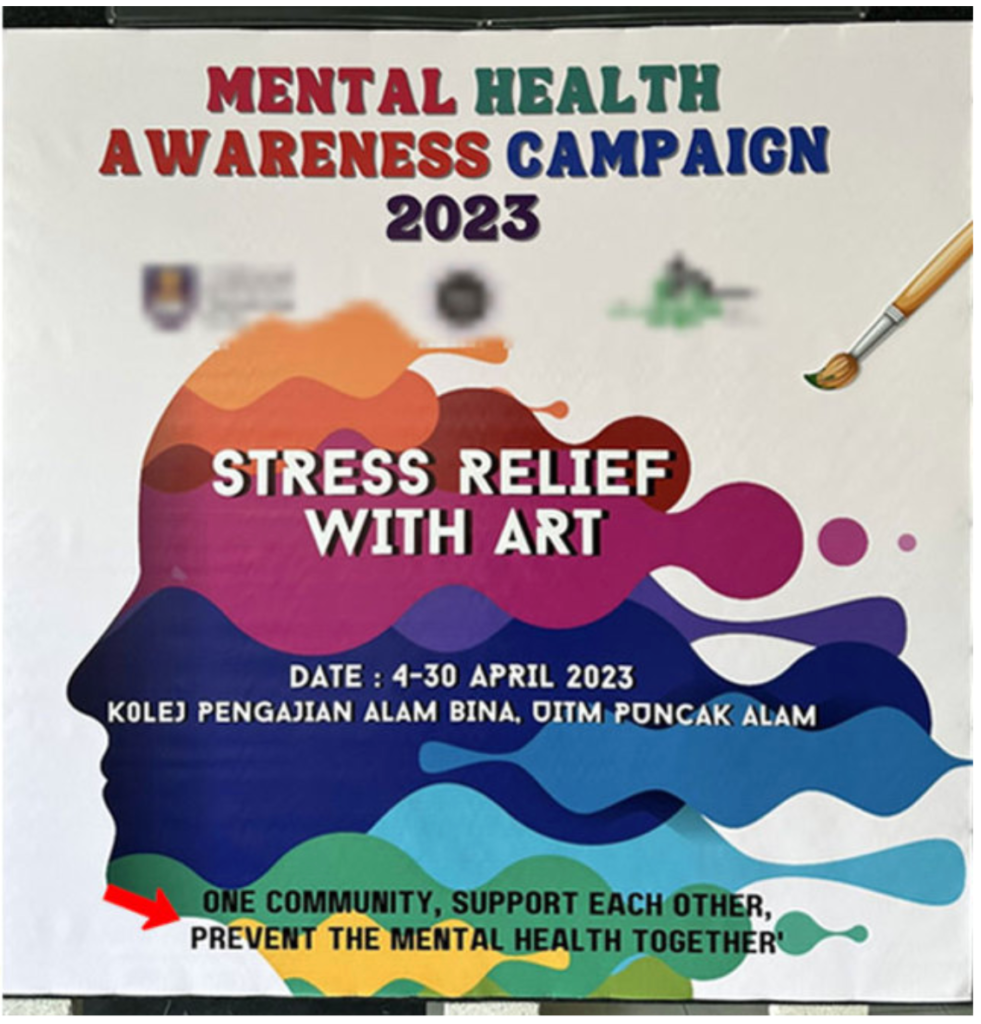

A poster advertising various events to be hosted by the College of Architectural Studies (KAB) at Universiti Teknologi Mara (UiTM) invited a barrage of criticism and much ridicule for its poor use of the English language.

One poster read, “Are you have a stress?”, while another referred to “doddle art” instead of “doodle art”.

The poster was roundly mocked by Twitter users.

One wrote: “No, I am not having stress, (I) am stressed looking at the poster.” Another said: “It’s a university… did anyone check the details, spelling, context, grammar, etc before promoting?”

In truth, no amount of proofreading or spellchecking will be of any use. A person whose English is poor and bad at spelling could look at the poster a hundred times and find nothing wrong with it.

It would be futile to blame our students for their poor command of English. Instead, we should blame the politicians, the system, the nationalists, and the teachers.

One could also blame our business leaders. Many noticed the steady deterioration of the English language and have been especially reluctant to employ our Malay graduates simply because they are the ones found most wanting.

Did these business leaders warn our politicians about the decline? Or did they keep quiet because they did not want to rock the boat?

This decline in English proficiency did not happen overnight. It has been going steadily downhill for several decades.

Our nationalists are eager to protect the national language and will mock those who speak English by questioning their patriotism. They are prepared to sacrifice the students’ command of the language without thinking about their future.

The students themselves ought to know that for their English to improve, they must speak the language regularly. After all, practice makes perfect.

Our teachers are bogged down by the system which in turn is determined by the politicians and their never ending flip-flops over how English is to be taught in schools.

Switching from English to Malay then back to English does not provide continuity. It has also affected the teaching fraternity significantly.

Politicians do things with the end-purpose of getting more votes. Being seen to protect the national language means that education policies are also crafted along racial lines.

Malays are brainwashed from primary school to believe that only the national language is important. As a result, few want to learn English. The consequence of this is felt when as young adults, students are unable to secure employment in the private sector.

Promoting Bahasa Malaysia is a vote winner among the Malay electorate. To prolong their political careers, politicians have sacrificed our children’s futures.

What is more remarkable is that other members of academia throughout Malaysia have been largely quiet about our students’ low proficiency in English. Why is this?

Are the lecturers petrified of speaking out for fear of being sacked or seeing their careers stall?

The teachers’ union also appears to be in denial.

Just think of the confusion among the students. On one hand, their lecturers tell them that they should become more fluent in English.

On the other hand, politicians tell them that Bahasa Malaysia will supersede English in communication. Who is right?

So who do you think one should blame for the error-strewn UiTM poster? Surely not the student who drew it up, since he is the product of poor policy by politicians who lack a long-term vision.

The views expressed are those of the writer and do not necessarily reflect those of FMT.

In the piece, Mokhtar highlights the role that the education system has upon students, highlighting conclusions about how flip-flopping in the education system, racial considerations, and a terrified populace of hemming and hawing academics whose priorities of self-preservation infinitely outweigh their desire to facilitate change. These damning factors, Mokhtar argues, have led to a confused generation of students who are unable to utilise their strengths because of the external environment around them.

Now, don’t get me wrong – I think it’s important to have these conversations, as they are the conversations that drive change forward in our society; how else would people take our politicians to task and get them to form more enlightened education systems that can facilitate the development of a generation that can compete in the market that is increasingly internationalised and has no regard for national borders?

At the same time though, there is a right way of having these conversations and also a wrong way – in my opinion though, Mariam Mokhtar? Your piece is one of many poorly-reasoned examples of criticisms of English proficiency of our generation. I think it actively harms our society and our national discourse, and its publication has failed to benefit the Nation in any meaningful way.

The problem?

Let’s go through the way that Mokhtar builds her argument. Before that though, let’s look at what she was looking at before she created her piece and also what she essentially based her entire argument on.

I’m not gonna lie – it’s kind of funny. Still, the way that Mokhtar builds her argument? Tremendously problematic.

Moving forward from these incredible examples of masterful rhetoric, Mokhtar’s barrage proceeds as such:

Because these students students wrote extremely poor English and “In truth, no amount of proofreading or spellchecking will be of any use, a person whose English is poor and bad at spelling could look at the poster a hundred times and find nothing wrong with it.”. Therefore, by this woman’s logic, it is futile to blame students – we should blame politicians who want votes, teachers, nationalists, and the education system.

…

…

…….

…

Whoa there lady – HOLD IT.

While I can see how the existence of the posters could lead to an evaluation that the individual(s) who produced this and the people who QC’d it aren’t very good at English… But Ms. Mokhtar’s reasoning seems to me to be very thin, and exceptionally low in quality.

First of all… Why did she assume that no amount of proofreading and spellchecking would be of any use, when it was Twitter users who noticed that there were mistakes in the posters? Did she just conveniently forget that?

Second of all… The students who produced the posters are individuals. They are not an entire institution, and they are not our entire country. Why and how did Mokhtar go from this set of examples towards generalizing all of Malaysia and blaming politicians as a whole?

You see, the entire way that Mokhtar has framed her argument is that because the poster exists, we should indict the education system for producing students with such low English proficiency.

Her words are horrible, damning, a white-knight move to fight for justice and to rail nobly against the crooked politicians and a self-preserving education system…

If you don’t know how to evaluate what you are reading and your critical thinking skills are weak.

Now what Mokhtar has said sounds very beautiful and plausible – if you read it only with a cursory eye to attention and minimal regard for detail.

Read it again and you will realise that her argument demonstrates flaws in statistical reasoning.

Mokhtar’s core argument is based only on a single example, and that example says nothing about the collective or average English proficiency of our generation and that it demonstrates numerous flaws that cannot be cleanly or easily addressed.

Mokhtar cites the problem of the poster in the University, but says nothing about the thousands of people who pointed out the floor in the poster and had the conscience and insight to highlighted for the few of the public – in fact, she probably found the poster because there was a sufficient critical mass of people who are aware of the glaring mistake that was present in the poster to the extent that they had the capacity to call it out.

What, are the students who created the poster somehow more Malaysian than the hundreds of other people who retweeted the post and called it out?

It’s interesting how Ms. Mokhtar somehow failed to notice this point, but simply utilizes the image to justify the particular breed of popular vitriol that is so common in the Malaysian civil discourse today about a nation that lacks English proficiency, serving as fuel for poorly informed Malaysians with poor capacity for critical thinking to go on social media and share the article, highlighting the downfall of English proficiency of an entire generation without even questioning their own.

It is patently and grossly unfair, unreasonable, and frustrating to watch someone who is supposed to be an allegedly intelligent social critic use a single example like this in order to make a broad generalization about the Malaysian public at large, and even more unfair to use it as a justification for the idea that hardworking teachers are failing to serve the students that need help or that they and politicians are solely to blame for Malaysian students’ average English proficiency.

Read it again, and you will see that this piece is grammatically flawed in ways that cast doubt on Ms. Mokhtar’s capabilities and credibility as a commentator upon the current state of the English language in Malaysia.

To illustrate this, I would simply like to draw attention to an error that is most clearly displayed at the top of the article.

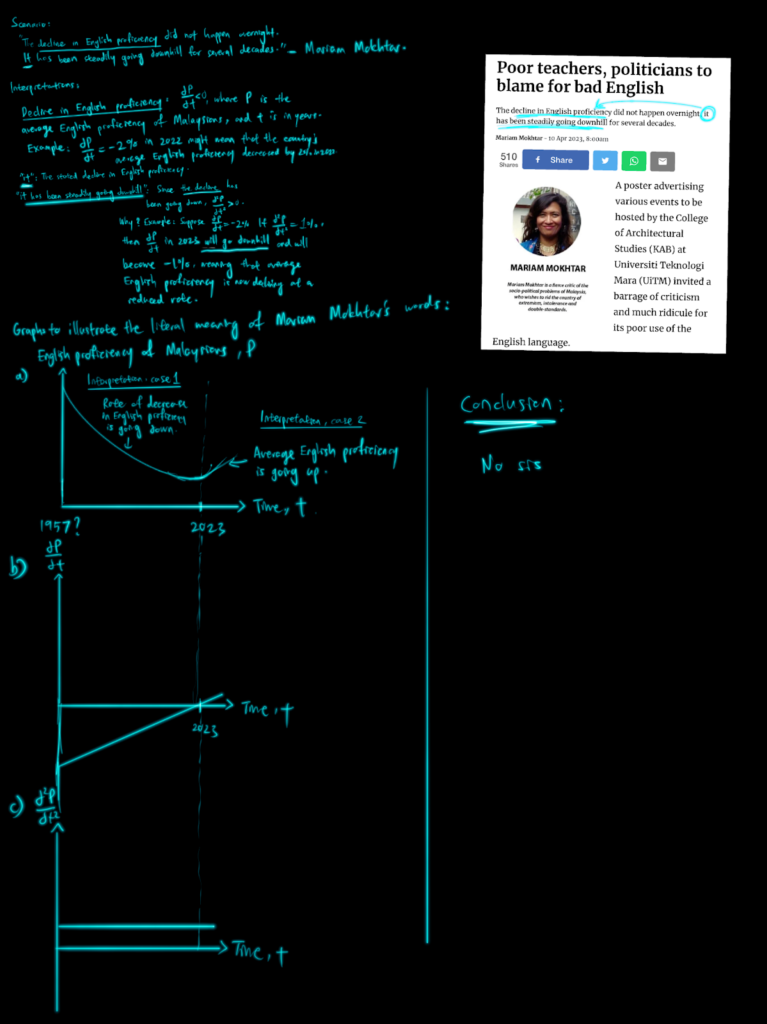

“The decline in English proficiency did not happen overnight, it has been steadily going downhill for several decades.”

Let’s interpret these beautiful words in the way that they have been written, using formal English language analysis.

To do this, let’s consider the role of the word “it”.

The word “it” is the example of what we call a pronoun – a word that may be used to replace an instance of a noun or noun phrase that has previously been used (what we call an ‘antecedent’) in the communication between a a reader and a writer.

It is crucial that a reader or listener be able to correctly identify what a pronoun is referring to, because that is crucial to words understanding any and all sentences that contain the word.

Let me give you an example.

Suppose I were to say the following:

“It is black, blue, and purple with some hints of white, and covered in granola.”

Would you know what I was referring to?

No, you would not.

You would probably ask:“What is black, blue, and purple?“, or a similar question, for the simple reason that you have no idea what I’m actually referring to.

On the other hand, if I had showed you this picture before saying the sentence…

“Here is a delicious blueberry and blackberry parfait. It is black, blue, and purple with some hints of white, and it is covered in granola.”

…The meaning of ‘it’ would immediately be obvious to you – ‘it’ refers to “a delicious blueberry and blackberry parfait”.

Why did the meaning of ‘it’ suddenly become clear? That’s because sufficient information was provided to us by the context in the case with the image, and sufficient information was provided about the antecedent for us in the case where the sentence “Here is a delicious blueberry and blackberry parfait” was provided.

Let’s take a look at what Mariam Mokhtar said once again in light of what we’ve discussed.

“The decline in English proficiency did not happen overnight, it has been steadily going downhill for several decades.”

– Mariam Mokhtar

Let’s ignore the comma splice and look at the more crucial antecedent reference that Mokhtar made when she declared “it has been steadily going downhill” in her sentence. Here, in order to understand what she has said, we need to identify what “it” refers to – in this case, “it” clearly refers to “the decline in English proficiency”.

The sentence continues with “has been steadily going downhill”, which indicates that the decline has been going down, and moreover that the double negative here implies that what Mariam Mokhtar has said is either:

- English proficiency in Malaysia has been declining and continues to decline, but at a slower rate.

- English proficiency in Malaysia has been improving.

In both cases, it looks like what’s happening is that uh, English proficiency is… Getting better?

I don’t think that’s what Mokhtar intended to say, and neither do I think that we should interpret her point as such… But if she intends to criticize the English language capabilities of the population, should she not demonstrate these capabilities herself?

Here’s a look at some calculus notation, in case you’d like to geek out and think about this (I also teach advanced statistics and econometrics):

In order to illustrate why this is objectionable, I’d like to quote a proverbial expression that goes as follows: “Those who live in glass houses shouldn’t cast stones.”

This proverbial expression highlights the idea that people should not criticize others for faults or issues that they themselves possess.

In this case, it would be hypocritical for someone to criticize others for poor English language usage while not maintaining a high standard of English themselves.

Ms. Mokhtar’s argument demonstrates a poor mastery of the English language and therefore it is ironic that she has presumed to be the one to hold the torch that will illuminate the course forward of our generation; seeing as she is subject to the flaws that characterize the very thing that she was criticizing, I cannot help but think of her article as an instance of the blind leading the blind all the way into oblivion.

Read it again, and you will see that her argument demonstrates a narrow and poorly reasoned perspective that is ultimately detrimental to society.

Let’s recall how Mokhtar ended her banger of a piece.

“So who do you think one should blame for the error-strewn UiTM poster? Surely not the student who drew it up, since he is the product of poor policy by politicians who lack a long-term vision.”

If you feel that you’re terrible at the English language yet you agree with Mokhtar…

You’re saying you believe it’s not your own fault for not putting in enough effort – it’s the government’s for not supplying enough teachers to you, or teachers of a sufficiently high quality.

You’re saying it’s not your fault for not reading effectively or taking the time to look deeply into developing your critical reading skills – it’s the teachers’ faults for providing you with books, and the politicians’ faults for not ensuring that everyone gets a private tutor on the caliber of the finest instructors in the world.

You’re saying effectively that it doesn’t matter what happens at home or what you do – none of it is applicable to you because it doesn’t matter anyway and it’s not your fault for failing to strategize.

Now, let’s move out of that foolish fairy paradise for a moment and head into the realm of reality.

I think you know that there is no way that we as a society should absolve individuals from responsibility and thereby lead them on a slippery slope that will allow them to blame external things rather than take responsibility for their own development.

I think you know that while we should push our education ministry to level up and provide better textbooks, teachers, and environments, it is foolish and meaningless to spend time making senseless generalizations that unjustifiably demean our educators and mock the efforts of our best and brightest, rather than taking meaningful actions to improve our individual mastery of the language so that in every single scenario within our sphere of concern, we are able to make a positive and meaningful difference through logical thinking and intelligent rhetoric.

I think you absolutely know that willpower and interest deeply affect how well a person learns English and that as a society, we should not promote the idea that people are owed improvement when that couldn’t be further from the truth.

Let me be clear that I think an education system is incredibly important and I’m not trying to diminish Mokhtar’s main points about how entrenched interests have made English a hard subject to advocate for…

Yet at the same time, let me say that while it is true that the education system has a great responsibility in cultivating the students of a generation, it is not solely responsible for the outcomes that each student will receive throughout the course of our lives.

You and I know, dear readers, learning how to speak the English language well is not easy. The reason that you are here is most likely that you want to improve your mastery of the English language – on the other hand, some of you come from far away to read these posts because you see value in this initiative and are interested to support it; few of you would probably imagine that you could avoid individual responsibility when you are talking about how you got to your current level of mastery and proficiency.

You and I know, dear readers, that English proficiency is something that is developed throughout the course of many years as a result of a person’s individual investment of time and energy into the development of this skill through their own time and interests, perhaps also through repeated and conscious interactions with their own family or friends over the course of time in the English language.

To say that it is solely politicians and the education system that are to blame for poor English proficiency is to completely absolve individuals from their crucial role in developing the capacity to speak the English language on their own, to say to the student who does not study that it is not his fault that he cannot speak the language, to mock the efforts of anyone who has ever had a burning wish to become more skilled at the vital skills of rhetoric and argumentation that are so important in modern society today.

It is completely at odds with how any single one of us who have learned the English language have managed to become good at it, it is passing the buck, and it is casually glossing over the true story of how a person can get good at the English language: Hard and intense work, ideally buoyed by a good environment, and undertaken amid a culture that facilitates respect for and a belief that progress is possible in the development of our English language proficiency as a whole.

By contrast, Ms. Mokhtar is saying that work is irrelevant when your teachers and politicians are bad, the environment is all that matters, and she is perpetuating a situation where people feel that it is right to mock and castigate those of us out there who are making a genuine effort to improve the situation from her little ivory tower off in Australia where she wrote this low-effort and lower-quality column that seems only halfway proofread and ultimately barely even registers as coherent.

She is planting the seeds for a culture whereby people just mock Malaysians and our capacity to articulate ourselves in English on bedsoil of shoddy evidence, flawed reasoning, and poorly-written English.

How ironic, considering that the apparent purpose of her piece is to promote English proficiency in Malaysia.

*Breathe*

Dear readers,

People who live in glass houses shouldn’t throw stones.

In this strange situation, we have a person with sub-par English proficiency criticizing people for what she references as their sub-par English proficiency, encouraging these people to increase their English proficiency by saying that it’s not their fault and that they should blame society for problems that they could and very much should take the effort to resolve through their own efforts.

Moreover, this person is tremendously influential, and people simply share what she has written without even questioning it, without even thinking about their own English proficiency, without even exercising any critical thinking about the content of the article.

Am I the only one who sees a problem with this?

Surely not, right???

Criticisms are ultimately like homing pigeons that come back towards us, for the simple reason that they will simply fail to hit their mark.

At the very least, I would hope that someone who is as influential as Ms. Mokhtar would demonstrate a minimum level of self-awareness and a level of insight that reflects her influence.

But that’s not the case – hence this piece.

I’ve pointed out the problems with Ms. Mokhtar’s arguments because I think that what she’s said demonstrates the average level of criticism that Malaysian civil society almost always displays when we as a society talk about the issue of the English language and go around in circles to discuss how well we’re doing or we’re not.

I’ve pointed out the problems with Ms. Mokhtar’s arguments because I’m tired of the way that many of us in Malaysia play a blame game that involves us passing on the buck to different people and stakeholders everywhere, because we either aren’t willing to admit that somehow or another there is a role for the individual, or we demonstrate poor reasoning on a societal level that is furthered by poorly reasoned opinion pieces like this that we share without reading, reacting to shoddy opinion pieces like this by instinctually calling out institutions, schools, politicians, and many more, exercising poor discretion and a lack of effective judgement, reasoning on the basis of limited examples or our own subjective thought processes by confirming what we had already believed rather than attempting to gain new insights by actually looking at the improvements that have been made or the advances that have taken place in our education system to make things better.

I’ve pointed out the problems with Ms. Mokhtar’s arguments because as a country, we need better thinkers than her to actually point out the problems that we need to solve before taking action to solve them, and refrain from listening too extensively to someone who doesn’t even live in Malaysia and demonstrates too low a standard of critical thinking to deserve the right to influence our thoughts and opinions to suit her ends.

Let me not be understood as saying that we should stop criticizing Malaysia as a whole. No. Not at all. What I am saying is that we need better critics of our Malaysian sociopolitical discourse, and we need thinkers who can call these critics out when they fail at what they are trying to do, not blindly accept and parrot their thoughts.

Some of the thoughts and points that Mokhtar has raised are valid. Certainly politicians and educators play a vital role in determining the future of our young ones, and ensuring that both the correct education system and the correct teachers are in place to teach our students is incredibly important.

But has Ms. Mokhtar actually attempted to perform an investigation with data about how bad the problem of a lack of English proficiency truly is, rather than simply making sweeping and irresponsible statements based on her subjective experiences?

The answer to that question, based on what I can see in this piece, is an irrevocable and irrefutable NO.

I appreciate that she has tried to serve as a critic for Malaysia, and I appreciate that she has her own agenda for how she wants to do it, but this was a horrible and poorly reasoned article that deserves not acclaim but instead an expression of horror from civil society.

English proficiency is a much more complex matter than what Mariam Mokhtar has described, and while it’s possible that the factors that she has described persist, it’s vital to not just blindly accept the claims that she (or any other thinker) has made merely because they sound plausible, but rather to consider the way that it has been reasoned out and the way that it has been argued.

Conclusion:

To close, I’d first say that there is insufficient justification for Mariam Mokhtar’s claims that politicians are the main reason that average English proficiency in Malaysia is going downhill, that we should not take her seriously, and that we should move beyond the blame game and into a phase of developing intelligent strategies to improve English proficiency for students both nationwide and worldwide.

Let’s merely say for the sake of argument that what she has said regarding a decline of English proficiency on a nationwide level is true; that would be a charitable interpretation that doesn’t hold true, but supposing that it is… Even in a universe where it is true that our nationwide English proficiency is decreasing on average, it is irresponsible and wrong to claim that politicians and educators alone are responsible for such a nationwide decrease in English proficiency. Politicians and educators are not solely to blame for any decline of English proficiency that we can witness.

However, let’s not sidestep the issue of English proficiency and how it is affected by government, the education system, and nationalism.

It is true that an education system is tremendously important for providing the resources, support, information, and guidance that students need to excel in the English language, and it is also true that good educators are required to create the circumstances for students to flourish.

We may think of this education system like an ocean, and students as boats; if the ocean is smooth, the boats can move forth with no problems whatsoever, moving forward on a course that allows them to traverse forward effectively.

Of course there can be good oceans, and there can be bad oceans as well – A good boat may traverse a bad ocean and travel a far distance, yes, though that is no indication that a good education system (operationalized as a smooth ocean with a good coast guard, navigational facilities, safety features, and established routes that facilitate forward movement) is in any way undesirable.

Yet, it is crucial to remember that while be good boats may buoyed by things such as talent, discipline, hard work, and a will to persist… yet at the same time there can be bad boats that lack the qualities already mentioned and therefore cannot traverse the distance that it requires.

I believe, as an educator, that the English proficiency blame game is unproductive and undesirable, for we cannot divorce any question of improvement in English language capabilities from a question of what we as individuals are doing in order to improve those capabilities on our parts, to develop, and to take responsibility for our own learning.

I took Mariam Mokhtar’s words as antithetical to that belief and unshakeable conviction, and this piece reflects my response to it.

If you read this to the end, I’m impressed!

Thank you for reading, and I look forward to seeing you in my next pieces ahead!